The student-run COVID-19 testing center, which got up and running in record time, offers an inspiring blueprint for the future, nursing experts say.

When Mark Tanner came to GW’s Virginia Science and Technology Campus weekly to get tested for COVID-19, the former assistant dean for the bachelor of science in nursing program parked adjacent to Enterprise Hall. He entered the building, scanned his GW badge, and walked up to the registration desk, where nursing students scannedQR codes on testees’ phones to call up their appointments, verify names and birth dates, and scan test tubes that would contain their samples. From behind plexiglass, the students—who were gloved and masked—wrote Dr. Tanner’s name and birth date on the test tube and verified his identity with his GW ID or license.

Dr. Tanner took his test tube and walked down a hall in the building’s former cafeteria, which was sufficiently capacious to accommodate the center, to one of six testing booths. If it was a busy time of day, he could wait a few minutes, but often he went right in. He would hand his test tube to the nursing student (gowned, gloved, and clad in an N95 mask and face shield), and the latter verified his birth date. Dr. Tanner had taught many of these students in first-semester didactic courses, but the students would invariably stick to protocol.

“Every experience I had, they always ask, ‘Hey. How are you? Have you done this before?’ even though they knew who I am, and they knew I’d done it before,” he said. “They’re doing the things that they should be doing. They’re neither relaxing nor taking anything off. There’s a sense of pride knowing they’ve come to our program; they’ve come this far; and they’re doing well with this very important task.

Each time, the student explained the procedure to Dr. Tanner, directed him to sit and drop his mask below his nose, and swabbed 10 seconds per nostril. The student nurse placed the swab in the test tube, broke it off and capped it, and then Dr. Tanner was ready to go. A courier picked up samples twice daily from the site, at noon and at 4 p.m., for delivery to Foggy Bottom for processing in a GW lab. Dr. Tanner usually had his results, which he could check via a mobile application, within about a day.

“It’s been very well and smoothly run,” he said. “I’m rarely there for longer than 5 to 10 minutes from the time I stand in line until the time I’m back in my car.” There’s a huge amount that happens in a very short clip, and the testing center did that more than 500 times per week at its peak. But equally as impressive is the speed with which the COVID-19 testing center was created and launched and how effective it has been during these difficult and uncertain times.

An ‘Aha Moment’

When GW announced in March 2020 that it would be going virtual, the School of Nursing was already well poised for online instruction, which it had been doing previously, but clinical placements became a problem when area hospitals said they couldn’t accommodate student-nurses. The Commonwealth of Virginia ruled that simulations could count for clinical experience, so that semester’s students could graduate.

“But then the new group comes in. What do you do with the new group? Summer, fall, and now spring. We really were beginning to scramble a little bit,” said Karen Drenkard, associate dean of clinical practice and community engagement.

By early summer, Dr. Drenkard was representing the Nursing School on GW’s pandemic task force and was co-running the task force’s health and wellness subcommittee. As the university moved toward bringing essential community members back to campus, there was a need for a COVID-19 surveillance polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing program. Two testing centers were created in Foggy Bottom—one for symptomatic and the other for non-symptomatic people—and by mid-August, Dr. Drenkard had a mandate to create and operate a testing center on the Virginia campus for the 550 faculty, staff, and students, who reported there for work.

“I’m not sure when we had the aha moment, but it’s 25 miles away, and the students have their clinical labs in Ashburn, the employees work in Ashburn, and we have housekeeping staff, faculty, students, and essential staff that are all going to be there,” Dr. Drenkard said.

The semester was slated to begin some two or three weeks after the Nursing School received direction to start the testing center, so Dr. Drenkard—who had only been at GW for about a year—needed to move very quickly. The former chief nurse who spent a decade at the five hospitals of the Inova Health System, had served also on the Northern Virginia regional emergency preparedness disaster task force for the hospital alliance right after September 11, 2001.

“I had a lot of disaster management experience, and I had operations experience,” she said.

Dr. Drenkard corralled a group, which included people she hadn’t met before and who hadn’t met one another, and oriented everyone toward the goal and looming deadlines. “We were able to break down a lot of barriers very quickly,” she said. She also brought aboard two people with whom she had worked previously and upon whom she knew she could count.

She enlisted Bonnie Sakallaris—who was chief nurse of the Alexandria, Va., hospital system and had worked with Dr. Drenkard at Inova—as the COVID-19 testing center director. “She was thinking that she was going to retire. I called her on Aug. 12 and said, ‘Would you be interested in doing this with me? I have no idea how long it’s going to last, but it’s going to be crazy. Do you want to come with me?’” Dr. Drenkard said. “She called me back in two hours and said, ‘Yes. I do.’”

“When you’re a nursing executive or a hospital administrator in the executive suite, you stand up new programs frequently, and often without a whole lot of notice. I had never opened up a testing center before, but both Karen and I have on multiple occasions, with very little notice, developed a whole new program, staffed it, and opened it up,” Dr. Sakallaris said. “There are organizational things that you know you have to do. This was not foreign territory.”

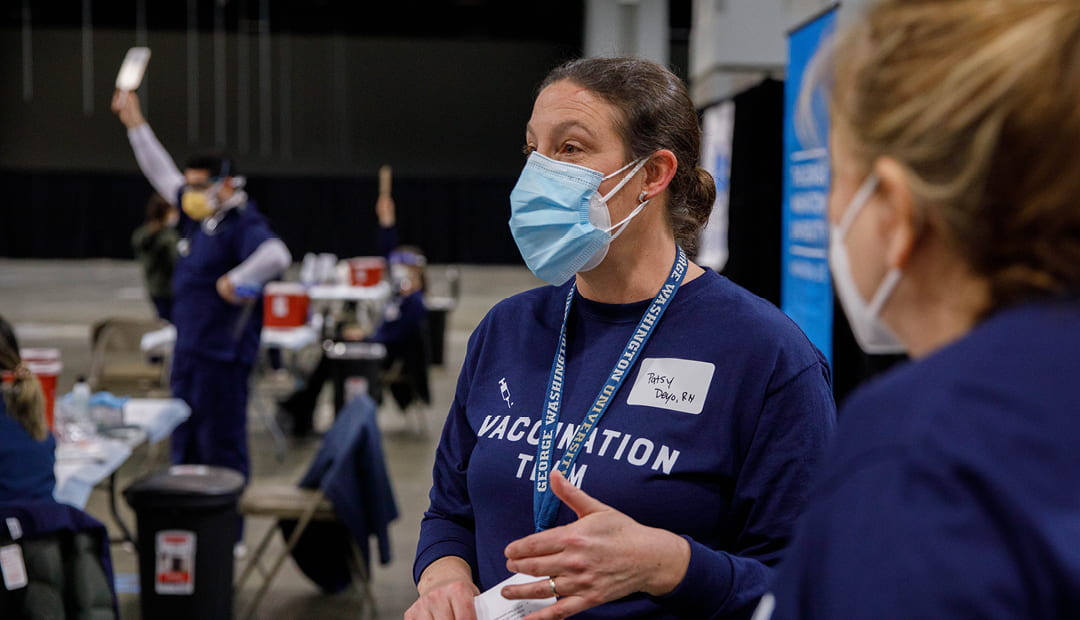

Dr. Drenkard also hired Patsy Deyo, M.S.N. ’14—who is in her Ph.D. dissertation phase in translational health sciences at GW’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences, and who worked previously in academic affairs at the Nursing School—to run student-nurse educational training.

“I knew we could do it. I wasn’t sure how,” Deyo said with a laugh. “There were so many moving pieces and so many different things that had to happen in such a short time that anywhere along the lines there could have been hiccups that would have impacted our being able to do it.”

The group secured supplies (including the highest level of personal protective equipment, PPE, that it could to protect the student nurses), drafted colleagues from different parts of the university, and found ways to involve students. (It also created and ran a flu vaccination clinic adjacent to the COVID testing center, as a “one-stop shop,” for two weeks in October.)

“I said, ‘If I’m going to put students who aren’t licensed yet in a situation where they’re exposed to some people who could possibly have COVID, they have to have N95s, face shields, gowns, and nitrile gloves,” Dr. Drenkard said. “We used very stringent infection control, and none of my testers ever got COVID.”

From the start, staff members were very open with the student nurses, asking how the process could improve and what challenges could be foretold and skirted. “We kept modifying what we did based on what they were seeing and said, ‘No idea was too crazy or far-out to try,’” Dr. Sakallaris said.

Students have expressed to Dr. Sakallaris something quite similar to how she feels herself: that as the pandemic unfolded, she felt drawn to the front lines to do something useful and to be part of the solution.

“This offers that opportunity,” she said. “It’s very gratifying to know that you’re doing something really important to manage and eventually stop this pandemic. That feels really good. It’s fun to see a plan come together.”

And though the group went into creating the clinic expecting there would be great lessons but also initial glitches, the process went surprisingly smoothly from the start, according to Dr. Sakallaris. “There was no chaos,” she said. “It was all really well controlled.”

Charge Nurse

Throughout the day—10 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Mondays and Thursdays, and 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on Tuesdays and Wednesdays—student nurses rotate through three roles: registrar, tester, and charge nurse. One student is charge nurse in the morning, and another takes over after lunch. That person is in charge of ensuring the center has adequate inventory and supplies, oversees lunches and breaks, and enforces social distancing and masking protocols in the center. She or he also delivers test samples to the courier for transport to the Foggy Bottom lab.

Veronica Nguyen—who worked at the testing center during the spring 2021 semester—found it nerve wracking the first time she served as charge nurse. Only one other student from her group had held the charge nurse position before, and Nguyen trained with Dr. Sakallaris and with that previous charge nurse.

“You worry about keeping everyone happy and running daily operations as smoothly as you can,” Nguyen said. “Especially for someone with limited leadership experience, it can be daunting to delegate tasks and make decisions. However, developing my leadership skills in a setting like the testing center was incredibly helpful.”

Faculty provided a safe learning environment to facilitate student growth and development, and debrief sessions at the end of the day helped the team address collectively issues that arose during the day. “This time allowed me to reflect on my role and work with my peers to improve,” Nguyen said. “I’m thankful that the testing center created this role. These experiences can help us develop our leadership style and practice as we go into our jobs as full-time nurses.”

Working at the testing center also helped Nguyen bridge the gap between didactic knowledge and practical nursing skills. “The testing site represents a crossroads of our nursing education, training, and experiences at clinical. At the center, we can practice practical skills like properly donning and doffing PPE, participate in patient education, and learn among peers,” she said. “The testing site offers opportunities for team management and building leadership skills.”

Another student nurse who worked at the testing center spring 2021, Timothy Barksdale, also found that the experience connected directly to what he was learning in his classes. “I am learning about COVID procedures in all my clinicals and classes, so the PPE requirements and general knowledge is very intertwined,” he said. “This clinical has absolutely raised my confidence in patient care as a whole and with COVID specific protocols.”

When Seneka Lea worked at the center during that same semester, she discovered there’s a lot more to the center than just swabbing noses and scanning test tubes.

“I was surprised at the number of individuals tested at the Virginia campus everyday, and then more so at the Foggy Bottom campus. Before my experience, these numbers didn’t really mean anything to me,” she said. “But in understanding the importance of surveillance and contact tracing on preventing outbreaks in our GW community, it is impressive to see how many individuals we test on a weekly basis.”

Lea learned something different from each of the three roles at the testing center. As a tester, she learned to ensure sample quality and to reassure patients (nasal swabs aren’t fun, she assures). As registrar, she fine-tuned customer service skills and attention to detail. And as charge nurse, she learned the importance of teamwork and assuming responsibility.

Normally—when it’s not a pandemic—student nurses don’t get a lot of primary care experience, because their clinical experiences tend to focus on acute care.

“This is a real chance for them to see how a primary care, very-specialized clinic works, and to see all the roles that go into making it happen. It gives a different experience than we’ve been able to provide in the past, and it really allows them to understand the full picture of what’s going on,” Dr. Tanner said. “It’s a hopefully once in a lifetime opportunity to work through a pandemic and to provide this service.”

Student Innovations

In addition to their assigned roles as registrar, tester, and charge nurse, students also kept their eyes and ears open and made an impact on important parts of the testing center processes, center staff said.

One nursing student read the label on a sanitizer bottle and questioned testers taking the swabbed specimens where they needed to go and only then coming back and sanitizing chairs. The instructions said the sanitizer had to sit for a minute before cleaning to be effective. After the student approached staff with that realization, the center process changed. Now, testers spray the chair and let the sanitizer sit while they deliver the specimen. By testers’ return, the sanitizer has done its magic and is ready to be wiped down.

On another occasion, students got the idea to help Spanish-speaking facilities and housekeeping staff on the Virginia campus understand more about COVID in their mother tongue. One of the students, who was fluent in Spanish, provided the text for the educational materials. “The students felt that it was very important to do this project,” Deyo said. “It was so well received.”

“The students were really picking up on knowledge deficits among groups of people coming in to get tested and were able to put together educational materials to address that,” Dr. Tanner said. “They served a really good role. They were the ones who noticed that and brought it to the faculty, who were overseeing and working with them.”

In another instance, students suggested minimizing the distance between the donning and doffing site and testing booths, so they wouldn’t have to walk through the entire testing center in full PPE. A new, closer space was identified, with the students’ help, and students set it up, sanitized it, and arranged supplies, Deyo said.

In normal times, students have less of an opportunity to bring fresh sets of eyes and ears in their clinicals and to provide feedback that revolutionizes processes, according to Dr. Tanner.

“Absolutely, there are people who may have those ideas, but the nature of this being a new clinic, really gave them more a sense of freedom to go ahead and say, ‘Hey. I’m seeing this,’” he said. “When you’re a student and you’re going into a well-established clinical site, you see something, but you may wonder why they do that. You may ask that question, but it’s not going to be very typical—I certainly know that as a student I wouldn’t have felt comfortable being like, ‘Hey. You guys should change this.’”

Looking Ahead

As Dr. Drenkard thinks back on all that GW was able to accomplish with its COVID testing, she thinks the university sits squarely in the top tier of those who showed leadership in pandemic management and surveillance. “The capacity to stand something up quickly and to use students who are in clinical training as a resource—these are all really important assets,” she said.

Dr. Drenkard also thinks that the testing center broadcasts an important and broad message about nursing. “As a profession, we’ve struggled a little bit to really shine as leaders, and this was an example of a combination of so many things going together,” she said. “Nursing and nurses taking on leadership and a nurse-led testing site and center shows what can happen and shows people what nurses are capable of.”

There will almost certainly be testing in some form over the summer, and the hope is that need will greatly reduce by the fall.

Now that COVID vaccinations are more prominent, the testing center has shifted to reduced hours. But there is still a potential role the center will play in vaccinations going forward.

It was able to do that with a flu vaccine clinic that the Nursing School stood up adjacent to the COVID-19 testing center, which provided flu vaccines in two weeks to everyone reporting to the Virginia campus who wasn’t already vaccinated. “The thing that we could really look at and see how we can incorporate is working on vaccination clinics,” Dr. Tanner said.

“It’s great to know we can do it on such a short time frame and make it effective. We hope that we don’t have to do it again that quickly,” he said of the COVID testing center. “Academics are made to move kind of slow and deliberate; it’s not the same thing as the clinical environment. But knowing that we were able to do that is a great thing to know and if we have a similar situation—which goodness I hope we don’t—it’s great to know that we were able to do that.”

Dr. Sakallaris agreed. “There’s going to be another crisis at some point, so this is the lesson that I would take away from that: When there’s a crisis looming, take a look at what your students can do, what can they learn from this, and how can we marry those two things. I think that’s been the most valuable thing,” she said.

“When there is a crisis, when there is something new going on, it’s a significant opportunity for learning for your students. Use that. Staffing this with student nurses is unique,” she added. “Other places have tested college students, but they’ve used contract labor and that sort of thing. I don’t know of any other place that has used their student nurses.”

And, of course, their flu vaccination clinic is likely to return in future flu seasons, as it has operated in the past. “It is a really good opportunity for student nurses to do IM (intramuscular) injections,” Deyo said.

AUTHOR Menachem Wecker