A School in Transition

When she applied to teach at the George Washington University, Crystel Farina, Ph.D.(c), RN, CNE, CHSE, knew very little about the School of Nursing or the university. “I applied solely because the dean was Pamela Jeffries,” said Ms. Farina, director of simulation and experiential learning.

A doctoral candidate at Notre Dame of Maryland University, Ms. Farina joined the Nursing School in August 2017. She had been aware of Dr. Jeffries, Ph.D., RN, FAAN, ANEF, FSSH, and her work on simulation since 2004, when Ms. Farina was teaching at Chesapeake College in Maryland and grew interested in simulation and nursing education.

“She was the one in all the articles who was teaching me how to actually do simulations,” Ms. Farina said of Dr. Jeffries, whom she first met in 2015 at the National League for Nursing’s Leadership Development for Simulation Educators. Dr. Jeffries was one of the “giants of simulation,” who formed a faculty group leading the program.

“It was like seeing a rockstar,” she said. “Oh my gosh, it’s her!”

Dr. Jeffries, who recently stepped down as dean at the School of Nursing—a role she held from 2015 to 2021—to become dean of Vanderbilt University’s nursing school, turned out to be “very down to earth, very relaxed, and very warm and fuzzy,” Ms. Farina recalled.

“I applied solely because the dean was Pamela Jeffries. She was the one in all the articles who was teaching me how to actually do simulations.”

– Ms. Farina

“Once I got over the awe of sitting with the godmother of simulation, it was very easy to have a conversation and talk about what we were doing at the college level, what we needed to do for nurse practitioners, and simulation in health care education,” Ms. Farina said.

This characterization of Dr. Jeffries as a down-to-earth, amicable rockstar is a common refrain among those who know and have worked with her. And the dean’s departure to Nashville, Tenn., comes amid a larger transitional time at the school and at GW.

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many best-laid plans. From an academic and administrative perspective, the School of Nursing was lucky to have put certain programs and processes in place prior to the pandemic, which helped mitigate some remote- and digital-only growing pains.

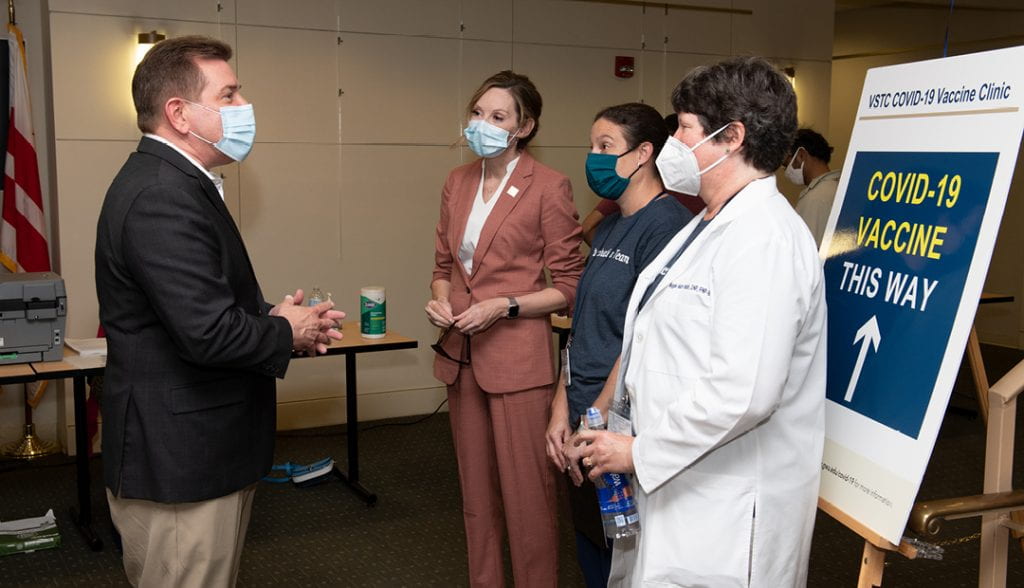

Pamela Slaven-Lee, D.N.P., FNP-C, FAANP, CHSE, senior associate dean for academic affairs and clinical associate professor, now serves as interim dean of the School of Nursing. GW recently announced that Mark Wrighton, chancellor emeritus at Washington University in St. Louis, will begin serving as interim president in January and will fill that role for up to a year and a half.The School of Nursing was about two-thirds of the way into its strategic plan when the pandemic began, requiring that in-person activities shut down in mid-March 2020. Despite this hurdle, the faculty and staff were able to fulfill the goals of that plan. And, although her departure was eminent, Dr. Jeffries saw to it that the next strategic plan was in place before she left. As she and her colleagues reflect on her legacy and vast achievements at GW, they see a bright future for the school, which has already earned national accolades that are more typical of much older and more mature schools.

The View from ‘Athens of the South’

Reached by video chat in Nashville, Dr. Jeffries said she hopes people will look back on her GW legacy as six years of bringing the school to another level. “We grew—maybe from adolescence to young adulthood,” she said.

Dr. Jeffries is very proud of starting GW’s doctoral nursing program and building up the breadth and depth of the school’s research base. “It still needs to grow more, but the quantity and quality of our research efforts have definitely scaled up,” she said. She also takes pride in the school’s No. 22 ranking for nursing graduate education by U.S. News & World Report and successful school-wide health policy branding.

Six years ago, when Dr. Jeffries came to GW—after serving as vice provost for digital initiatives at Johns Hopkins University, and before that as an associate dean at Hopkins and at Indiana University Bloomington—her priorities were to build upon the foundation her predecessor, Jean Johnson, established as founding dean some five years prior. Having inherited high-quality programs, Dr. Jeffries wanted to take the school to the next level.

“I had an analogy of a three-story house. Dr. Johnson built the first floor. I had the second floor, which continued to build on our reputable programs,” Dr. Jeffries said. “To build the research base on the third level, I wanted to start a Ph.D. program and to diversify revenue, because we were very tied to tuition dollars and enrollment numbers.”

Dr. Jeffries started a professional development office called Ventures, Initiatives and Partnerships (VIP), and she sought to improve the school’s national rankings. She aimed in five years to move the school into the top 25 graduate programs in the U.S. News & World Report rankings. (It previously ranked No. 58.) It took six years, but the school bested that goal by three slots.

“I had an analogy of a three-story house. Dr. Johnson built the first floor. I had the second floor, which continued to build on our reputable programs,”

– Dr. Jeffries

In the 2022 U.S. News rankings (the Georgetown-based publication ranks schools based on the prior year’s data, which can sound like predicting the future), the Nursing School is also tied for No. 28 in the category of “Best Nursing Schools: Doctor of Nursing Practice” with Oregon Health and Science University; University of California, San Francisco; University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; and Washington State University.

In the U.S. News specialty nursing school rankings, the GW School of Nursing is No. 8 in “Best Master’s Nurse Practitioner: Family,” and is tied for No. 6 in “Best Master’s Nursing Administration” with University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And in the U.S. News online nursing program rankings, GW is No. 2 for “Best Online Master’s Nursing Programs for Veterans,”No. 3 for “Best Online Master’s Nursing Administration Programs,”No. 7 for “Best Online Master’s Nursing Programs (tied with University of Nevada, Las Vegas), and No. 7 for “Best Online Family Nurse Practitioner Master’s Programs.”

Creating a doctoral program to help train nursing scientists was necessary to become a top-tier school, according to Dr. Jeffries, who also is proud of starting the school’s Center for Health Policy and Media Engagement. The latter draws upon the school’s location in the nation’s capital.

“I don’t think I would have changed anything if I could have read the tea leaves and known COVID was going to hit in March 2020,” Dr. Jeffries says. “In fact, we actually prepared ourselves not knowing it was happening.”

Pivoting Online

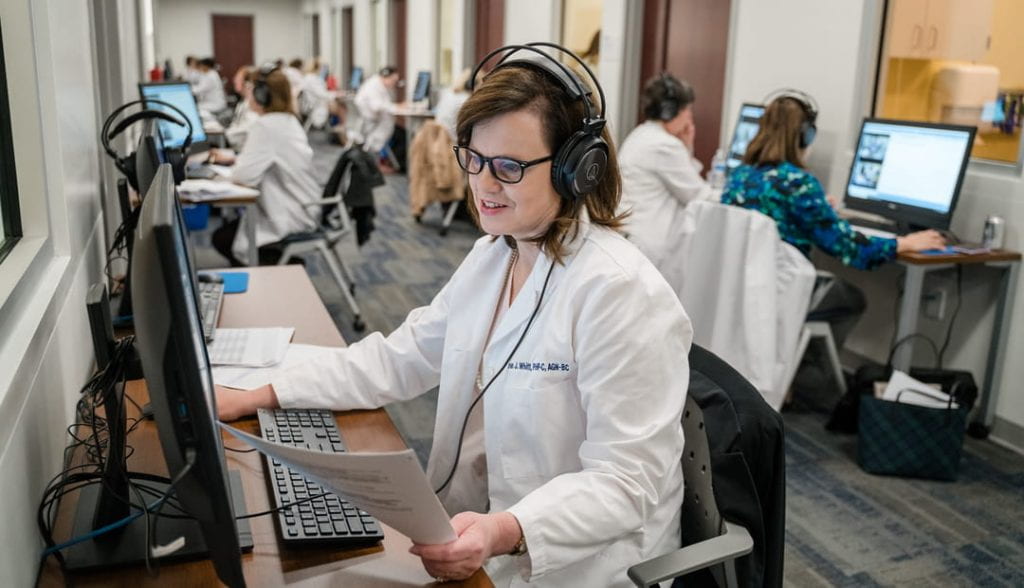

Prior to March 2020, the Nursing School had already begun assembling the necessary personnel to strengthen its creation and delivery of online programming. Dr. Jeffries hired e-learning specialists, instructional designers, videographers, a graphic designer, and a director of online learning and technology.

“I’m glad that was done, because that served us well in COVID,” she said. “We already had online education going at GW Nursing, but I put more resources and support into building a team.”

She also brought on a team to help run the expanded simulation center on the Ashburn, Va., campus, home to a state-of-the-art Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) center. “They had to pivot during COVID to produce and really facilitate faculty with the virtual simulations,” Dr. Jeffries said. And after lockdowns ended, that team facilitated safe in-person lab simulations.

During the pandemic, Dr. Jeffries would wake up each morning and ask herself what she needed to get through the day.

“I built community with our faculty, staff, and students,” she said. There were weekly town hall meetings for nearly 70 weeks, and Dr. Jeffries helped staff leaders, who had never managed people remotely, and professors, who could not see their students in person, navigate the new normal.

“We did keep community together,” she said, noting the school’s instructional continuity in particular. “Our students graduated on time for the most part.”

“Some of us thought—I was one—we could come back in three or four weeks,” she said of the beginning of the pandemic. “I stayed very focused to get through. I always had to hold it together. Someone has to be the leader.”

Looking forward, Dr. Jeffries notes that telehealth is poised to be a game changer for the profession, and she expects the pivot online will continue even after the pandemic is in the rearview mirror. There is a need for telehealth competencies and full integration into curricula, she said, and nursing schools ought to teach students to assess patients via digital platforms, such as Zoom. Patients are also increasingly tracking their own health data, something nurses should take advantage of.

“We’ve got to be mindful of that,” Dr. Jeffries said.

She looks forward to continuing to see the School of Nursing’s programs flourish, as well as new programs emerge. She expects the healthcare landscape to continue to change, and thinks public health is a priority, particularly the focus on health equity that COVID exposed, as outlined in the National Academy of Medicine’s report “The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity.”

“I see the next five years as a little different. Right now we are transitioning in COVID, but we are still in COVID. But our antennas are up for different things,” she said. “I think we’ve learned we can do things differently.”

Big Shoes to Fill

Dr. Slaven-Lee, now interim dean, came to GW two months before Dr. Jeffries did in 2015. She was excited to join a young school, about five years old, and the opportunities that its youth presented. Dr. Slaven-Lee served previously in a leadership role at Georgetown University and looked forward to returning to teaching. That was not in the cards, however.

“Dr. Jeffries developed our matrix structure with two communities and academic programs, and made a lot of infrastructure changes. With that, it opened up a lot of leadership opportunities,” Dr. Slaven-Lee said. “I came here saying, ‘I want to go back to teaching and not so much leadership.’ As is often the case, I ended up back in a leadership role.

”Dr. Slaven-Lee worked closely with Dr. Jeffries on developing the simulation program, which “became a signature part of our academic programs,” and building the academic affairs unit. “Really further developing all the things that you do as your school continues to mature—evaluation plans, standardizing how you evaluate your academic programs, master plans of evaluation, standardizing how you evaluate each course, clinical placement models, all those sorts of things,”she said.

In the past six years, Dr. Slaven-Lee has seen GW’s reputation soar and has noticed changes in the applicant pool. She does not think anyone else applied for the same job she did in 2015, but now, “The caliber of the candidates that we see trying to come to GW and join our faculty community is outstanding.”

Part of that, she thinks, is the national recognition the school has received in rankings. “Considering how young the school is—we’re 11 years old—that’s absolutely remarkable that we’ve been able to accomplish that,” she said.

Since becoming interim dean on July 1, Dr. Slaven-Lee has drawn on what she learned from working with Dr. Jeffries, whom she called “a great mentor.” She also is very focused on the school’s strategic plan.“

The strategy I have in my mind is to stay focused on the school. Stay focused on our students, faculty, staff, and strategic plan,” she said. She is also focused on enhancing the curriculum with an eye toward diversity, equity, and inclusion, she said, as well as the “Future of Nursing”report.

“The caliber of the candidates that we see trying to come to GW and join our faculty community is outstanding.”

– Dr. Slaven-Lee

“It’s not just, ‘Hold everything steady until a new dean comes.’ It’s ‘Continue on the upward trajectory.’ Holding things steady would be a disservice to the school. We’ve got to keep things moving upwards,” she said. “I’d be derelict in my duty if I just tried to hold things steady. When you’re ranked 22, that takes some work. You can’t just hold steady. You’ll fall backwards.”

Dr. Slaven-Lee expects the school’s rankings to continue to improve, and like Dr. Jeffries, she anticipates that there will be online and hybrid programming and teaching in the future. She also echoed Dr. Jeffries’ thinking about the school’s unique role in the heart of Washington, D.C.,and in northern Virginia.

“We want very much to brand and distinguish ourselves as the school of nursing that’s about health policy,” she said, noting that most GW School of Nursing researchers focus on health disparities and inequities.

“The juncture where it all starts coming together is the research informing the policy informing the practice. It’s not something we are trying to be. It’s something we are actually becoming,” she said. “We want to leverage our position in the nation’s capital.” The school also developed a dual Master of Science in Nursing and Master of Public Health degree, which matches renewed interest in that intersection.

She aims, she said, to fill Dr. Jeffries’ big shoes.“Dean Jeffries is an incredible leader. She is very well known for being a great communicator. She always had a vision,” Dr. Slaven-Lee said. “She did so much in the just six years she was here.”

The Power of Simulations

Dr. Slaven-Lee, Dr. Jeffries, and Ms. Farina—the director of simulation and experiential learning, who chose to apply to work at GW because of Dr. Jeffries—all point to simulation as one of the areas of greatest change at the School of Nursing in the past five years.

Dr. Slaven-Lee said it was “absolutely pivotal for the development of our programs” to require all faculty to be trained in best practices for simulations. “Simulation is a pedagogy that is incredibly powerful. By virtue of that, if it’s used inappropriately, it can have negative impacts on the students’ evaluation and development,” she said.

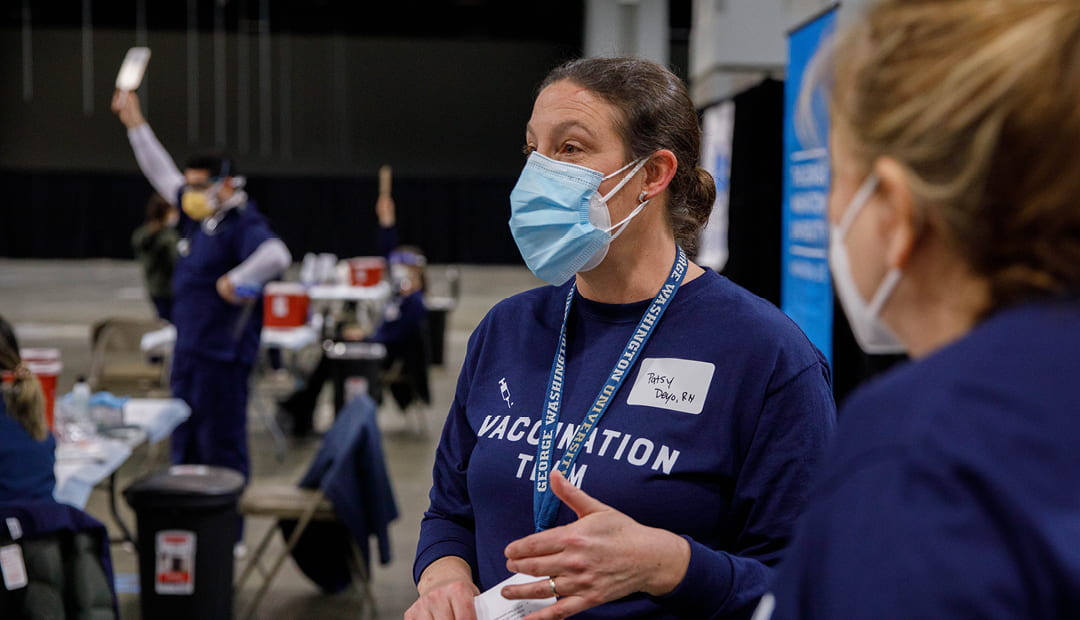

Simulation training on campus is also a signature event for the school and for students. “These are big events. That’s how they know the campus. It’s about developing alumni. We’re known in the community for being expert simulationists,” she said. And many professional societies and vendors come to GW for talks on best practice simulation.

“It’s not uncommon to see a whole panel of GW faculty talking about simulation,” Dr. Slaven-Lee said.

Ms. Farina’s tenure at GW has seen sustained growth in the school, she said. When she began working at the school, there was summer enrollment for the first time; there had only been spring and fall terms previously. And some of the conferences and other events that provided the most momentum in pushing the school forward centered on simulation.

Much of that success is owed to Dr. Jeffries, who played an essential role in securing funding for renovations of the simulation center and for expanding its offerings.

“She was really supportive in ensuring that I had the authority to request that all faculty had a standard of education for simulation before they came and facilitated simulation experiences,” Ms. Farina said. She noted that Dr. Jeffries was also involved in creating a massive open online course (MOOC), in which more than11,000 learners have enrolled and participated.

GW Nursing School students now do a lot of virtual and face-to-face simulations, and the curriculum is aligned with didactic content, skills labs, and simulations.“It’s all lined up that way so that they can apply everything they learned each week to providing simulated patient care,” she said. “They sit in lectures; then they learn a few skills; and then they are able to apply all that knowledge to providing care for that simulated patient.”

Ms. Farina hopes the nursing program continues to expand and thinks the school has a shot at top 10 in the U.S. News rankings. She also expects the school to become, in the next two years, one of 2,000 accredited by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. “It shows that our simulation is high fidelity, high quality,” she said of that accreditation.

Collaborative Culture

Majeda El-Banna, Ph.D., RN, CNE, ANEF, had previously taught at several nursing programs, large and small, stateside and abroad—including Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, where she was dean of the School of Nursing—before arriving at GW in 2013. She began as adjunct professor and is now associate professor, chair of acute and chronic care faculty community, and director of the Registered Nurse to Bachelor/Master of Science in Nursing (RN to BSN) program.

“GW really attracted me with the mission and vision,” she said. And when she started teaching at the school eight years ago, “I said, Oh my goodness!This is the place where I want to be.” She has been extremely happy at GW since.

Where some of her colleagues may think the School of Nursing’s growth has been meteoric, Dr. El-Banna, who has taught in nursing programs for more than 20 years, was part of one school that tripled in size in two years. That was a little more of a dramatic pace than she has seen at GW.

Still, when she first arrived on campus, the nursing program was small enough that communication could occur in a more ad hoc fashion. As the school grew, there needed to be more formalized processes.

She credits Dr. Jeffries’ establishment of the Ph.D. program as a very significant and difficult feat, and the faculty communities that Dr. Jeffries pioneered—the school’s take on departments—have facilitated growth, cooperation, and mentorship. When Dr. El-Banna compares Dr. Jeffries’ approach to communication between faculty and staff, spread across the Foggy Bottom and Virginia campuses and many others remote across the country, to those she has observed at other schools, she thinks what the School of Nursing has achieved is remarkable in this regard.

During Dr. Jeffries’ tenure, faculty was encouraged to collaborate on research, and research funding increased. A buddy system paired new hires in their first year with seasoned colleagues who helped them acclimate to GW. And the dean also welcomed faculty, staff, and students to her home regularly, including for holiday parties.

“GW really attracted me with the mission and vision. I said, Oh my goodness! This is the place where I want to be.”

– Dr. El-Banna

“How did she have the time to hold so many social events in her house?” Dr. El-Banna wondered. “That is different from other schools.”

The “culture of collaboration” at the School of Nursing is one of the things that attracted Dr. El-Banna initially, and which has kept her happily at the school. Dr. Jeffries would ask faculty members where they saw themselves in a few years, and once she knew their plans, would provide guidance on necessary future steps. She would also keep her eyes and ears open for future opportunities, which she would share with faculty.

“I don’t know how she remembers all the things about all the faculty,” Dr. El-Banna said. “It’s amazing.”

When she reflected more on the changes she has seen at GW during Dr. Jeffries’ tenure, and the culture she foresees continuing, Dr. El-Banna reached for an affable metaphor. “It feels more like a family,” she said.

AUTHOR Menachem Wecker